- Home

- Lakhous, Amara

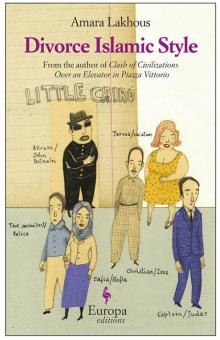

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942) Page 9

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942) Read online

Page 9

My “sister,” for instance, is very fond of the name Maria. Her husband is against it because he considers it a Christian name. She defends it energetically by pointing out that one of the wives of our Prophet was named Maria: she may have been a Copt, but she converted to Islam. So there would be no religious transgression—it would be in full obedience to tradition. The situation is serious. Is the marriage really in the balance? Don’t be ridiculous. Anyway, we hope that the newborn will be male so we can avoid this mess. I say goodbye to my “sister” Amel after the usual stream of advice for a pregnant woman, and I go to pay for the phone call. Waiting for the news on Al Jazeera I start talking to an Egyptian about the war in Iraq. My companion, a graduate in international relations, explains to me that the Americans’ objective is not to democratize Iraq but to destabilize Syria and, especially, Iran. What a grand discovery! Every knows it, even the camels of the Sahara. I pretend to listen to his analysis, every so often throwing out an observation or a brief comment. I don’t want to be taken for an idiot with nothing to say. In other words, it’s a two-way conversation, not a one-way lesson.

Anyway, I am open to all conversation, from politics to sports, from economics to history, from archeology to medicine. I’m ready to talk to anyone. The important thing is to socialize with as many people as possible. I try to play the part of a friendly young immigrant, carefree and outgoing, who likes to be with people.

At a certain point I take my eyes off the television screen, I look around, and who do I see? The girl with the veil. Luckily this time she’s not crying, in fact she’s smiling. She’s even prettier than before, with that colored veil. As she goes out, I try to photograph her in my memory. I even manage to see the cover of the CD she has in her hands: Om Kalthoum’s Awedt Einy, “I’m Used to Seeing You.” I decide not to follow her. I’m here on a very particular mission. I’ve got to get busy and try to find out the members of this damn second terrorist cell.

So far I’ve bought a lot of coffees and teas for quite a number of Arabs in order to grease the wheels of friendship. I have to say that I’ve done pretty well. The Egyptians are like Neapolitans: they know how to make themselves agreeable, or at least they make an effort; sometimes they succeed, sometimes they don’t. Certainly, they are incurable exhibitionists; they never want to go unnoticed. So they’re a bit touchy when they don’t receive the right amount of attention. With me they have no problems: I guarantee total concentration on what they have to say. They’re never tired of seducing you, above all with words. When they use Egyptian Arabic, which is known in the whole Arab world, thanks to the soap operas, they seem like consummate actors. A Tunisian girl once said to me, “Egyptians are never spontaneous, they always seems to be playing a part, with the script in their hand.” She’s right. They’re nothing like the Maghrebi. It’s hard for Middle Eastern Arabs to understand the Arabic of Moroccans, Tunisians, and Algerians

I have to interrupt my conversation with the Egyptian about democracy and the war in Iraq—Akram alias John Belushi is calling me.

“Tunisian!”

“Yes?”

“Are you still looking for work?”

“Yes.”

“Inshallah, there’s something for you. You want to wash dishes?”

Fantastic! A job possibility. I’ve done well to hang out here every damn day. Little Cairo is a strategic place. So many people come and go, as a result they exchange information of every type: apartments, jobs, possible legalization for illegals, couples in crisis, imminent marriages and divorces, and so on. Akram is really clever—he manages to intercept all this flow and use it to his advantage to augment his “commercial” power. My compliments!

The Egyptian explains that the dishwasher job is available immediately, so it would be smart to begin today. Then, it has one great plus: the restaurant is very close to Piazza della Radio. Sleeping over the store, so to speak: I won’t have spend hours waiting for the night bus. The crucial thing is to stay in the neighborhood, not get too far from Viale Marconi. Finally he advises me to go to the restaurant right away and ask for his friend the Egyptian pizza maker, the architect Felice. But what sort of name is that? And then, what the hell is an architect doing in a pizzeria!

“Tunisian, I’ve found you a home and a job.”

“Thank you, hagg Akram.”

“Now if you want I can find you a wife.”

“No, thanks. Mamma’s already taking care of it.”

“It’s time to give you a push. Remember that marriage is the goal of Islam.”

I thank Akram with a strong handshake. I get the directions and go to the restaurant without wasting any time. The place is nearby, and I arrive in a few minutes. I ask for the pizza maker, Felice. He’s just arrived.

“My name is Said, but here they call me Felice, my nom de guerre. Hahaha.”

“Nice to meet you, I’m Issa.”

“Akram spoke well of you. He said you’re O.K. In other words, different from the other Tunisians, who deal drugs.”

“Each of us is responsible for what he does.”

“Right.”

I don’t pay much attention to the stereotype of the Tunisian drug dealer. I was inoculated long ago against these shitty prejudices: the Sicilian Mafioso, the Neapolitan Camorrist, the Sardinian kidnapper, the Albanian criminal, the Gypsy thief, the Muslim terrorist, and so on and on. In Arabic Said means felice, happy. So it can’t be said that he has changed his name—he’s just found the corresponding Italian. Felice offers me coffee and we exchange a little information. He’s lived in Italy for twelve years, and has an architecture degree from the University of Cairo. That’s why they call him bashmohandes, architect. He still harbors dreams of someday practicing his profession. He’s married and has a small daughter. From the way he speaks, I understand that he’s very observant. He’s constantly quoting verses from the Koran and sayings of the Prophet. He’s like an imam. The arrival of the restaurant owner, a guy named Damiano, who’s around sixty, compels us to interrupt our pleasant chat. Felice introduces me, saying I’m a respectable young man. And now the job interview, or, rather, the interrogation.

“Where are you from?”

“I’m from Tunisia.”

“You speak Italian?”

“Yes.”

“You have documents?”

“Yes.”

“What’s your name?”

“Issa.”

“Why do you all have strange names? What does it mean?”

“It’s the name of Jesus in Arabic.”

“So you’re Christian?”

“No, Muslim.”

“You’re a Muslim and you’re called Jesus! I continue not to understand a fucking thing about you Muslims. Have you worked in a restaurant before?”

“No.”

“Don’t worry, it doesn’t matter. I just want boys who are serious, and on time, and don’t bug me. Understand?”

“Yes.”

“As you see, I’m not a racist. I don’t discriminate between Muslims and Christians, people with a residency permit and illegals. For me they’re all the same. Understand?”

“Yes.”

“Listen, I’ve already forgotten your name. It’s hard to remember. We’ll have to call you something else, what do you prefer: Christian or Tunisian?”

Obviously I choose the second. A Muslim who is called Christian is pure provocation. It would be like going to Mecca with a cross around your neck. I don’t have the slightest intention of running that risk.

I begin work right away, after accepting the owner’s conditions: two weeks’ trial and forget about a contract; that is, I work illegally from opening till closing. I think of my residency permit, so far it’s been of no help either for renting the bed or for the job. Who knows, maybe it will turn out to be useful for wiping my ass when I can’t find toilet paper.

In the kitchen I meet the three cooks: two Bangladeshis and a Peruvian. Besides Felice there’s an Egyptian pizza assistant named Fa

rid. The waiters, on the other hand, are all Italians. The customers have no contact with the immigrant staff. Is it a coincidence?

I finish work around two in the morning. Everyone has left except the boss, who is enjoying a last whiskey before going to bed. It will take some time to get used to the fact that among the duties of the dishwasher are the cleaning of the kitchen and the two bathrooms. In short, I’m also the housewife of the restaurant.

I go home dead tired. I fall sleep without any problem. The insomnia of the past few days seems to have disappeared by itself. I begin to understand something important: people who work hard don’t need sleeping pills to get their sleep. Those are for the rich, who don’t do shit from morning to evening. The usual war between rich and poor. “Cu avi suonnu nun cerca capizzu”—“When you’re tired you don’t go looking for a pillow.” This is called class conflict. Am I becoming a Communist? Don’t be ridiculous. It’s just the delirium of exhaustion.

Sofia

I’m sitting across from the Trevi fountain. It’s the middle of the night and no one is around. I see the big blonde (the one from La Dolce Vita) in the fountain, under the waterfall. Suddenly she starts shouting, in English, “Marcello, come here!” I go on watching, but I’m blinded by jealousy. Marcello Mastroianni is sitting there having coffee and he doesn’t make a move. I can’t bear it for very long, I take off my scarf and walk into the fountain. The water is freezing. Marcello puts aside his cup of coffee and gets up. I’m very surprised, because he’s looking not at the blonde but at me. I’m flattered. After a while he approaches. And when our gazes meet I realize that Marcello has the face of the guy with the tissue (the Arab without a name) whom I met first at Little Cairo and then at the Marconi library. After that I begin to tremble with cold. The Arab Marcello (from now on I’ll call him that) immediately understands that and embraces me very sweetly. I’m so happy. But the dream ends and abruptly I wake up.

Thank God I remember my dreams clearly, from beginning to end. And so? So what. I won’t have any trouble telling Samira. She is great at interpreting dreams—she always manages to get something important out of them. She often says, “The dream is an inner voice that comes directly from the heart.”

I get through the housecleaning in a hurry. Around ten-thirty I leave my husband sleeping soundly, as I do every morning, and go with Aida to the park in Piazza Meucci. When I get there I find Giulia and Dorina sitting on a bench chatting. Near them are two children playing on the swing, and Aida runs off to join them. Grandfather Giovanni is totally immersed in his newspaper. How strange! He’s reading Il Manifesto! What has happened in the world? Has he become a Communist? Why has he given up Padania, Libero, and Il Giornale? Life is strange. Nothing lasts forever, except God Almighty. I prefer not to say hello to him, in order not to disturb him. His reactions are always unpredictable.

I sit beside my two friends. I quickly discover the subject of discussion. Today we’re talking about breasts. About preventing breast cancer? No, about cosmetic surgery. Now that voluptuous bosoms are fashionable, many women (often they’re still adolescents, I’ve heard that the operation can even be a gift for high-school graduation) decide to remake their breasts in order to appear beautiful, attractive, or simply sexier. Giulia and Dorina are in favor of the operation. Giulia says, “What’s wrong with it? Today going to the cosmetic surgeon is like going to the dentist or the gynecologist.” Dorina agrees, “We live in 2005. A woman should be free to dispose of her own body as she likes.”

I myself have a different opinion, and since it’s impossible for me to remain silent, I have to interrupt to defend my convictions. My theory is simple: veils are not always pieces of fabric, there are tricks, comparable to our veil, that hide other parts of the body. And so? So what. In other words, the reshaped breast hides the original breast, the reshaped nose hides the original nose, the reshaped lips hide the original lips, and so on. I begin my sermon (I’m a good orator, one day I might even become a female imam!) with the health risks: how many poor breasts are ruined by operations? Unfortunately I don’t have statistics at hand, but the percentage of failures is high. Dorina and Giulia (now they’re speaking with a single voice) reply, “The cosmetic surgeon is a doctor like any other doctor, so it happens that every so often he makes a mistake. These are things that happen in every field of medicine.” On this point they’re not wrong. The medical argument won’t get me anywhere. I have to change my strategy and find something more persuasive.

I move to religion, a subject I know better; in other words, I’m still a believing and practicing Muslim. So the question is this: what is the position of Islam on cosmetic surgery? It is haram, illegal, if the surgery is not indispensable. Which means? If a person gets a broken nose in a car accident and can no longer breathe well he has every right to turn to a cosmetic surgeon to fix it. Here beauty has nothing to do with it. It’s a matter of health. Clear? Instead, if a woman looks at herself in the mirror when she wakes up in the morning and decides to touch up her upper lip because she doesn’t like it anymore, Islam says, “No, madame. You can’t.” Why? The reason is simple: our body doesn’t belong to us—the true owner is God Almighty. When we’re born we take it only in trust, it’s under our management for a limited time. In the end we have to give it back in good condition. Even tattoos are haram.

Dorina and Giulia listen to me with interest. I understand that my speech has hit the mark. I’ve got one line left before the curtain falls. You have to leave the stage in grand style and to applause. So here comes the finale. “Excuse me! What will a reshaped woman say to God Almighty on Judgment Day? I’m giving back the body that I had on loan. But . . . I’m sorry . . . the breast surgery didn’t go well.”

Giulia stares at me a moment before moving to the counterattack. “Judgment Day? What are you talking about, Sofia? You know what I say? I don’t give a damn about Islam, I’m not a Muslim. Well, all right, I’m a Catholic who remembers I’m a Catholic only at Christmas and Easter. In reality I’m allergic to all religions, without exception. I’ll do what I like with my body. Do you understand?”

Giulia’s words make a breach in the silence of our Albanian friend. “I don’t deny that I’m a Muslim, but in my private life I want to be free: my body belongs only to me. We say that God gave it to me. All right? And we can do what we want with this gift, or not? Otherwise what sort of gift would it be?”

Bravo Dorina! Solid reasoning, really. I’d never thought of the body as a divine gift. Anyway, the religious argument wasn’t a great idea for the case against cosmetic surgery. I’m an observant believer and I act accordingly. For Dorina and Giulia the situation is completely different. Let’s say they’re sailing in other seas.

To what point can we Muslims consider ourselves truly free? While I reflect on the meaning of freedom in Islam, Giulia won’t let go—she wants to have the last word. “Dear Sofia, you wear the veil, so you don’t need to show off a shapely bosom. Think of poor women like us, who can’t display a nice décolleté because of their flat chests, and so they get complexes.” And Dorina in support: “Who would ever have said? Even the veil has its advantages. You’re lucky, Sofia.” Me, lucky? Well, maybe, yes. Basically, why always be complaining? Dorina is very ironic. But I’m not joking, either, and when I start there’s trouble for everybody. “You want to wear the veil, like me? No problem. Please, make yourself comfortable. Welcome to the club of veiled women.”

More laughs.

Grandfather Giovanni, sitting on the bench next to ours, comes out of his isolation. Maybe we’ve disturbed him. He has the look of an angry person. Is he mad at us? It’s likely. He stares at us for a few seconds, then throws the paper on the ground, shouting, “Have you seen what those Communist bastards of the Manifesto write? They say that the partisans are heroes, patriots, the country’s saviors! I say they are a band of traitors. Yes, they are trai-tors. The ones who are still alive should be hanged and I spit on the graves of the dead. Goddamn Communists!”

The time passes quickly, it’s almost lunchtime. I have to go to the market to do the shopping. I like to wander among the fruit and vegetable stalls. Shopping is a career, in fact an art, as my father always says. There are important rules to follow. First, examine the goods very patiently. Second, don’t respond immediately to the solicitations of the vendors. Third, take the time necessary to choose what you want. Fourth, buy exclusively on the basis of the quality-price relationship. You have to be like a good hunter: strike at the right moment in order not to make a mistake. Maybe I’ve found my prey. This vendor has the best apples in the market. There are two people ahead of me. After a couple of minutes it’s my turn. As I’m about to speak a man of around fifty emerges out of nowhere and asks to be served first. I thought he hadn’t seen me, a simple and innocent lack of attention. I was wrong. And in a big way. The man looks at me disdainfully and says:

“I was here first. Do you understand Italian?”

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)