- Home

- Lakhous, Amara

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942) Read online

Europa Editions

214 West 19th St., Suite 1003

New York NY 10011

[email protected]

www.europaeditions.com

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2010 by Amara Lakhous

First publication 2012 by Europa Editions

Translation by Ann Goldstein

Original Title: Divorzio all’islamica a viale Marconi

Translation copyright © 2012 by Europa Editions

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Cover illustration by Chiara Carrer

www.mekkanografici.com

ISBN 9781609458942

To Vito Riviello (1933-2009)

A great poet and a dear friend

Since love and fear can scarcely exist together,

if we must choose between them,

it is much safer to be feared than loved.

—NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI

As for my irony, or, if we prefer, my satire,

I think it frees me from everything that irritates me,

oppresses me, offends me,

makes me feel uneasy in society.

—ENNIO FLAIANO

Issa

Finally, on a Saturday afternoon in the last week of April, I become operative. I take the 780 bus from Piazza Venezia and get off at Piazza della Radio. I walk to Piazza Enrico Fermi. There are too many cars—it would take a small miracle to find a parking place. The sidewalks are congested. People are drawn to the clothing stores like flies to honey or garbage.

I stop in front of a display window to stare at the reflection of my face. I’m struck by one detail: the mustache. It’s the first time in my life I’ve grown one, and I seem at least five years older. I’ve had my hair almost all shaved off, like a marine. For sure I’ll save on shampoo and gel! I got some cheap clothes, jeans and a sweater made in China, sending my usual look to hell. In other words, I’m unrecognizable.

For the umpteenth time I stick my right hand into the inside pocket of my jacket. No panic: the wallet’s there. But what’s happening to me? Am I afraid of being robbed like some tourist? Don’t be ridiculous. I just want to reassure myself that I haven’t lost my new identity papers—without the residency permit I’m an illegal immigrant at risk of expulsion. By now I’ve memorized all the new biographical facts. Starting today I have a new name, a new date of birth, a new citizenship, and I was born in a different country.

It takes me a little time to get into character. Meanwhile, I have to get used to this crummy mustache. I have the strange sensation of being inside someone else’s body, an intruder in my own skin. In fact, in Rome I really am a foreigner, it’s a city I don’t know well. I must have been here a dozen times, but always passing through. The first time, I came on a class trip. I know it as a tourist, no more or less. Of course, I can boast of having seen the Colosseum, the Trevi Fountain, Piazza Navona, Villa Borghese—just like millions of other people in the world.

And then I shouldn’t complain too much; feeling like a foreigner at this particular moment isn’t a handicap, in fact it’s a great advantage in playing my role. Of course, I don’t mean a role in a film—I’m on a dangerous mission. And I have no intention of playing James Bond or Donnie Brasco—I don’t have the physique for it.

I stroll around aimlessly for a good hour and a half, back and forth along Piazza della Radio and the Marconi bridge. I want to get familiar with the neighborhood right away. I observe the façades of the buildings attentively—the variety is impressive, like the faces of the people I pass. There are all types: young Africans and Asians selling counterfeit goods on the sidewalks, Arab children walking with father and veiled mother, Gypsy women in long skirts begging. In other words, I’m in the Italy of the future, as the sociologists say!

In these circumstances I’m like an animal in search of a new habitat. You have to conquer the territory with your teeth. I’m not greedy, I just want a little place in the shelter of Viale Marconi. Am I asking a lot? I don’t think so. I decide to go on the attack, like a tiger that has to feed its pups. The warmup phase has already lasted too long; I have to enter the game.

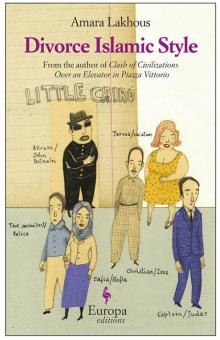

I leave Piazza Fermi and take Via Grimaldi to my destination. Now I’m in front of the call center. I glance at the big letters over the entrance: Little Cairo. O.K., here we are! I take a deep breath and enter resolutely, launching the first Arabic words of the day.

“Assalamu aleikum!”

“Aleikum salam!”

A fellow named Akram, whom I’ve seen in photographs taken in Mecca, responds. Akram is the owner of the place, as well as suspect No. 1. It’s likely that he’s the head of the first cell. He’s fifty, a bit chubby, wears an elegant white shirt. With sideburns, and a hat, glasses, and black shoes and pants, he’d resemble the legendary John Belushi. Like every good merchant he has a broad smile stamped across his face. You have to communicate trust and positiveness. Clients are like children, they always need to be coddled and reassured. On the wall at the left, high up, in the corner near the ceiling, is a television. It’s five, time for the news from Al Jazeera. There are at least four young Arab guys staring at the screen who look like they don’t want to be disturbed for any reason whatever. It’s not impossible that Osama bin Laden could appear in person to hurl new threats against the West.

I ask Akram if I can make a call to Tunisia. He nods his head yes and invites me with a finger to choose a booth (he can’t speak; he, too, is focused on Al Jazeera). Without thinking I choose No. 3, my lucky number. Captain Judas (I’ll talk about him later) provided me with a couple of numbers in Tunisia I can use that won’t rouse suspicions. Who am I going to be talking to? What will I say? I have no idea. It’s a real mystery.

I feel like an actor in a play who has to perform without a script. I have to improvise, I have no other choice. I dial the first number, it’s ringing. After ten seconds a woman’s voice answers and asks who’s calling. I have an instant of hesitation, then I say, “It’s Issa.” And she: “Wildi ya kebdi! My son, my little chick.”

Surprise No. 1: I have a second affectionate mother, who speaks Tunisian like me!

The conversation lasts ten minutes. We talk about this and that, from the health problems of the “grandparents” to “papa’s” business, from the latest news of “brothers” and “sisters” to changes in the weather.

Surprise No. 2: I have a nice big family, even the grandparents are still living! The end of the phone call is really moving, the list of instructions from an affectionate Tunisian mamma to her émigré mamma’s boy: “Don’t catch cold, don’t forget your Arabic, don’t trust women in general and European women in particular, don’t drink alcohol, don’t go around with hoodlums, don’t get into debt.”

I hang up and go to pay. I wait a bit, Akram is busy with two other clients. When my turn arrives I take out my wallet and give him a ten-euro bill. I add in a neutral tone that I made a call to Tunisia: I want everyone to know I’m Tunisian.

Akram, however, doesn’t give a shit about my country of origin. He looks at his idiot computer, where the cost of the calls is indicated, gives me seven euros in change, and goodbye and thanks. He wants to get rid of me like that, without even knowing who the fuck I am! No, I’m sorry, but that’s not for me. Friend, I’m not asking you to invite me to dinner at your house or go to a café and drink tea with me, but at least give me the chance to introduce myself properly. It costs you nothing. Am I a new client or not? Don’t I deserve a little respect? You’re a businessman, you should know that the cli

ent is always and everywhere king! Instead of going away disappointed and defeated I stand fixed to my spot.

“Can I help you with something else, brother?”

“Yes.”

That damn yes! I don’t know what to say! I have to invent something in a hurry. There’s the risk of looking like an idiot with Judas, who wants results, right away, and keeps repeating, like a parrot: “We’re playing in the Cesarini zone.” In other words, there’s no time to waste, the game is about to end.

Luckily, in extremis I get an idea.

“Could you make two copies of my residency permit, please?”

“Of course.”

Obstacle overcome. Luckily, I can continue. Before returning the document, Akram gives an extended glance, I would say exaggerated, to the contents. He doesn’t seem embarrassed. Ever heard of that shit thing called privacy? He has the look of a border patrol agent. Over the years I’ve seen plenty of these lousy cops at the airport!

I make the first move to break the ice.

“Don’t tell me it’s counterfeit.”

“No, it doesn’t seem so. I was looking at the address. You live in Palermo?”

“I did live there, not now. I moved to Rome a while ago.”

“You escaped Sicily because of the Mafia, eh?”

“You’re right, I really did escape, but because of the unemployment. Now I’m looking for a place to sleep and a job.”

“May God help you.”

“Amen.”

“My name is Akram, I’m the owner of the shop.”

“Nice to meet you. My name is Issa.”

“See you soon, inshallah.”

“Inshallah.”

My dear Akram, you’ll have me underfoot a lot in the coming days, God willing, or, rather, inshallah. It’s a promise I’ll keep. You can be sure.

After the introductions I feel calmer. I can take home the first results. I’ve made an appearance at Little Cairo. Nothing exceptional—no comparison with the Madonna’s appearance to the three children of Fatima. You have to keep your feet on the ground. The important thing is to avoid false moves or irreversible mistakes. And yet I can’t help thinking of what Akram said about Sicily. Will we ever manage to get rid of this Mafia label? The outlook isn’t good.

I was right not to talk too much to the Egyptian alias John Belushi. Judas urged me strongly not to be too friendly right away. There will be other occasions for socializing. Better not to be in a hurry, someone might get suspicious. Or, worse, I could inspire hostility at the first meeting, and after that everything would be more complicated.

I have to constantly remind myself that I’m Tunisian, and this neighborhood is full of Egyptians. Many people don’t know that there are rivalries among the Arabs. For example, it’s not smooth sailing between Syrians and Lebanese, between Iraqis and Kuwaitis, between Saudis and Yemenis, and so on and so on. It’s why they can’t seem to come up with a plan for unity, in spite of a common history, geography, Arabic, Islam, and oil. The model of the European Union will have to wait!

I leave Little Cairo and walk to the 170 stop on Viale Marconi. When the bus comes I find a seat near the window. As it heads toward Termini station I begin to reflect on the mission: was I right to say yes? Can I still abandon it? Will I measure up? Goddamn performance anxiety. I’m confused and a little agitated. Thoughts and memories surface without warning. I try to concentrate. I don’t know why, but my grandfather Leonardo comes to mind. We were really fond of each another. When I was small we’d sit looking at the sea, in Mazara del Vallo. He would tell stories and I’d listen for hours without ever getting bored.

He had enough stories to fill a stack of books. He was born in Tunis to a family of immigrants from Trapani. He had lived there until adolescence, before returning to Italy. In the last years of his life he wanted desperately to see the city of his birth. I would have liked to go with him. Sadly, he had heart trouble, so it didn’t seem like a good idea to revive those strong emotions, he wouldn’t have held up. And yet maybe what he wanted was in fact to be carried away by those emotions—to die and be buried in Tunis, beside his mother.

My grandfather was a splendid person. His stories were never melancholy; he always managed to avoid nostalgia, “the brute beast,” he called it. He wept only once, remembering his mother, who died when he was a child. It was he who taught me my first words in Tunisian Arabic: Shismek, what’s your name? Shniahwelek, how are you? Win meshi, where are you going? Yezzi, enough? Nhebbek barsha, I love you very much. And a lot of others.

In Mazara I grew up with the children of the Tunisian fishermen. We were always together, playing, fighting, and immediately making peace. I was often taken for one of them: I had typically Mediterranean features and I spoke Tunisian Arabic well.

I visited Tunis for the first time when I was thirteen, with my family. We took the boat in the late afternoon and arrived at the port of Tunis early the next morning. That night I couldn’t sleep, I was so excited. We stayed for two weeks. It was an unforgettable journey for me: I finally saw the land where my grandparents were born. Since then I’ve been back several times.

After high school, no one was surprised when I decided to enroll in the faculty of Oriental languages at the University of Palermo. I wanted to improve my Arabic. At the university I began studying classical Arabic; I was determined but also enthusiastic. I really liked the grammar, which drove everyone else crazy, not just the students but the professors. I was one of the best students, and a lot of people couldn’t believe that my native language was Italian.

I wrote my thesis on Giuseppe Garibaldi’s sojourn in Tunisia. The research was very difficult—I don’t know why I like complicated things so much! What does Garibaldi have to do with Tunisia, you ask? He does have something to do with it, he does. The Hero of the Two Worlds arrives in Tunis in 1834 to escape the death sentence for insurrection pronounced by the court in Genoa. He spends a year in the Tunisian capital under the false name of Giuseppe Pane, working for the Bey of Tunis. After that, he continues his adventures as a revolutionary in Brazil, where he supports the independence movements against the Portuguese and the Spanish. In 1859, he returns to Tunis, but the authorities deny him entrance when the French consul intervenes. For his local admirers Garibaldi continues to be a hero, a true revolutionary. For his detractors, on the other hand, he is merely an outlaw, a dangerous terrorist.

After I got my degree I often went to Tunisia, and I also had opportunites to visit other Arab countries: Algeria, Morocco, Yemen, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria. Obviously, people often continued to take me for a Tunisian, but I didn’t mind at all.

I would have liked to have an academic career, but a flunky no—I really didn’t want to be the professor’s servant and kiss his ass. I took several exams so I could study for a doctorate, but without getting anywhere. I quickly understood that the system was of the Mafioso type, with all kinds of godfathers, bosses, and affiliates. In other words there was nothing left for me. So I was satisfied with a job at the court in Palermo as an Arabic interpreter. Luckily, or unluckily, there are a lot of Arab criminals (mostly from the Maghreb), and percentagewise they have a large presence in Italian prisons. So there was never any shortage of work. Then Captain Judas arrived to turn my life upside down.

It all began a few weeks ago.

I was coming out of the courtroom during the lunch break when a guy in a gray suit came up to me; he was around forty, tall and lean. Right away I thought he was a new judge or a lawyer on a business trip.

He said to me in a serious tone:

“Signor Christian Mazzari?”

“Yes.”

“Hello. I’m Captain Tassarotti from the SISMI, military intelligence. I’d like to talk to you.”

The word “SISMI” didn’t scare me. In three years of work at the court it often happened that I worked with the antiterrorism squad. In particular I’d been asked to translate telephone wiretaps and propaganda flyers.

Together we

left the court. We got into a waiting car, and the driver immediately headed toward the sea.

The captain’s way of proceeding impressed me. He got to the point immediately, without beating around the bush; maybe he was in a hurry or maybe he had intuited my great need for coffee in order not to fall asleep. He started off with a sentence that left no room for doubts: “Signor Mazzari, we need you for a mission.”

He took a piece of paper from a file and asked me to read it carefully. I noted that the document, printed on letterhead and marked by various stamps, had many blacked-out lines. The letters, however, appeared to have been written on a typewriter.

Subject: Operation Little Cairo

Our services have received reliable information from American and Egyptian colleagues, according to whom a large-scale attack is being planned in Rome. Two terrorist cells seem to be involved in the operation. XXXXXXXXX up to now we have succeeded in identifying only one of them.

The subjects gravitate around Little Cairo, a call center in the Marconi neighborhood. The place is managed by an Egyptian citizen, xxxxxxx, and frequented by many foreigners, especially Muslims.

This information confirms the contention of the Western intelligence services that Al Qaeda has changed its strategy with respect to September 11th. Today it no longer relies on terrorists arriving for a mission but is taking advantage of the presence of Muslim immigrants in the West to commit attacks.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Al Qaeda has changed its strategy with respect to September 11th. Today it no longer relies on terrorists arriving for a mission but is taking xxxxxxx

The attacks of March 11, 2004, in Madrid fit into this new criminal design: the terrorist Jamal Zougam and his accomplices were for the most part Moroccan immigrants, apparently integrated into Spanish society.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxbe no risk to my safety, because the operation would take place not in the enemy’s camp but at home, in Romexxxxxxxxxxxx

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)