- Home

- Lakhous, Amara

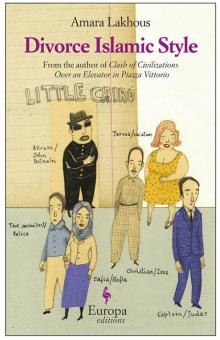

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942) Page 8

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942) Read online

Page 8

In the Muslim religion divorce is very quick. Two words are enough to sanction it: Anti tàliq, I divorce you! That is the formula for divorce. Usually it’s the man who has this power. The third time the words are uttered the divorce becomes final. After the first two times, it’s possible to reconcile, but after the third it gets a little more complicated. If the ex-husband wants to go back to the ex-wife, he has to marry her again. Exactly. But that’s not all; there’s another condition, or, rather, three. First, the ex-wife has to marry another man, who obviously has to be a Muslim (no Christians, Jews, Buddhists, and so forth), and the marriage has to be consummated. Only under these conditions can she then divorce and remarry her ex-husband. Clear? Not very.

O.K., I see the difficulty of explaining the matter to non-Muslims. I’ll try to be more explicit, but it means I have to talk about my private life. Unfortunately I myself have had experience of these unpleasant things. In five years of marriage, my husband and I have already passed the second divorce. In other words, my husband has already pronounced the formula for divorce twice. Both circumstances are vivid to me. Both times it had to do with arguments. The first goes back to a couple of years ago. We quarreled because I insisted on working as a babysitter. The second is more recent, and the reason is more serious. He wanted to have another child right away, and I didn’t. I needed to reflect before making such an important decision. My husband is a good person, but he has one big fault: he loses control easily. When he gets angry, he’s like a drunk, or rather a wild dog. Anyway, after the first and the second divorce he apologized, weeping. In both cases he admitted his mistakes. And what could I do? I agreed to let Imam Zaki mediate; he acted as a peacemaker, because he’s like a brother to me. In Cairo we lived in the same neighborhood, and his sister was a childhood friend of mine. I was thinking mainly of my daughter’s future. After the second divorce, Imam Zaki was very severe with the architect. He told him that divorce isn’t a game. He lingered a long time on the meaning of a quotation from the Prophet: “Among licit acts the most hated by God is divorce.” In the end he gave him a warning: “Look out, you’re playing with fire—the next divorce will be final.” Usually I try to listen to the imam’s words without commenting. But this time I couldn’t. “I’m certainly not the one who’s asking for a divorce, so the one responsible is him and him alone.” I said it in a tone of exasperation.

Now I don’t want to think about the third divorce, and especially its consequences. I believe deeply in maktùb, so I look to the future serenely and without worrying too much. And then the right to divorce in Islam is not exclusively the man’s; the woman can have it, too, in the rare cases where she is stronger in the marriage negotiations.

There’s one question that goes around and around in my head, and I can’t get rid of it. Why can a Muslim man marry a Christian or a Jew whereas a Muslim woman can’t marry either a Christian or a Jew? The five pillars of Islam are valid for both men and women. So why shouldn’t all have the same rights and the same duties?

After twenty minutes Dorina, our Albanian friend, joined us. She’s a Muslim like me but she doesn’t wear a veil. She’s the caretaker for Giovanni, an old man who has a lot of trouble walking. Dorina is twenty-nine and has lived in Rome for six years. She has a really terrible story. I’ll try to summarize it. She’s nineteen, living peacefully with her family in Tirana. She dreams of going to the university and studying medicine. One dark day she meets a handsome young man who courts her persistently, saying he’s madly in love with her and wants to marry her. Dorina trusts him, falls in love, especially when the young man officially asks for her hand (a soap opera Albanian style?). After a couple of months she agrees to go on vacation with him in Italy. From that moment the romantic dream turns into a nightmare. Dorina discovers the truth: the fiancé is a ruthless criminal who uses the promise of marriage as bait to lure beautiful girls into his trap. Dorina is sold as a slave to a criminal gang and forced to work as a prostitute. After four years of torture she finds the courage to report her exploiters, with the help of an organization that fights the prostitution racket preying on immigrant girls. So she gets her residency permit and moves to Rome to change her life. She has never gone back to Albania because she’s ashamed, she’s afraid of how people will react, and also that her exploiters might take revenge. Now Dorina hates men, all men, and she often cries when she recalls freezing nights waiting for clients on the outskirts of all those cities. I always try to cheer her up.

Grandfather Giovanni is over eighty, and has some hearing problems. But in my opinion he’s not quite right in the head. He usually sits on a bench, the same one, reading La Padania, Libero, and Il Giornale. You’re in trouble if you disturb him, even just to ask the time. You have to leave him alone. After he finishes reading, he bursts out with comments like: “I hope I die before Romania enters the European Union”; “Soon we’ll be invaded by the Gypsies, they’re like locusts, and we’ll have migrant camps everywhere, even right outside our houses”; “What’s the government waiting for to close all the mosques and throw the Muslims in jail?”; “If the Muslim immigrants really want to assimilate, they should convert and become Catholics! I want to see them at Sunday Mass!”; “Damn Communists. It’s always their fault.” The finale is almost always the same: “Oh, my country, so beautiful and so lost!”

Grandfather Giovanni calls me “sister.” I’ve told him over and over, “I’m not a nun, I’m a Muslim.” And he answers, “What? You dress like the sisters and you’re not a sister?” I try to persuade him: “I can’t be a sister, I have a husband and a child.” And he: “I see, the Muslims are mad for women. They even marry sisters!” I don’t have the least desire to explain to him that nuns don’t exist in Islam and that the Prophet Mohammed strongly advised against monasticism. Among us people say, “Marriage is half religion,” or “Marriage is prevention.” Many transgressions are linked to sins of the flesh, to sex. When someone marries it becomes easier to hold temptation at bay. But perhaps this applies more to men than to us women, or am I wrong?

Once Grandfather Giovanni made me practically die laughing. After the usual reading of the newspapers he stared at me for ten seconds or so, then he fired off questions like a high-speed train.

“Libero says that the Americans are resigned: they won’t get bin Laden alive or dead. Excuse me, sister, I would like to ask you a question.”

“Please, Signor Giovanni.”

“This damn bin Laden, where is he hiding?”

“I don’t know.”

“What do you mean you don’t know, sister? He can’t have disappeared into thin air. Have you hidden him somewhere, the way you did with Saddam Hussein?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t know anything about it.”

“All right, all right. You don’t trust me because I don’t belong to your religion. You know, I was in the war, so I’m an expert in military matters. You see, I have a hypothesis on bin Laden’s hiding place.”

“Really?”

“Bin Laden is a Saudi, right?”

“Right.”

“So he’s hiding in Mecca, in that square mausoleum you call Ka . . . Ka . . . Kamikaze or . . . Kawasaki.”

Fantastic! An ingenious hypothesis. The Kaaba, built by Abraham, has become a motorcycle brand! But poor Giovanni is only a parrot, he repeats the stupid things he reads in the papers. Luckily he’s almost deaf. Every cloud has a silver lining! What garbage would come out of that mouth if he could follow the programs on TV and radio.

Before going to the market to do the shopping I stop off at the Marconi library to borrow a book or a movie. The staff are all women, who are polite and kind. I choose a book of fairy tales for Aida. Then I go up to the second floor to glance at the newspapers. I see the young man with the tissue, the Arab without a name. I pretend not to notice him. He is looking at me.

Around noon I go home to make lunch. After we eat, the architect plants himself in front of the TV for another round with Al Jazeera. Sometimes I thi

nk of Al Jazeera as a real rival, a sort of daytime lover. He spends more time with her than with me. And so? So what. Maybe I’m starting to become a jealous wife. Should I be worried?

At four my husband leaves the house to go to work. The second part of my free time begins. I take Aida and go to see Samira, my best friend. We live in the same building—all I have to do is go down one floor. For me she’s like a big sister. Samira is Algerian; she’s ten years older than I am, and has lived in Rome for fifteen years. She’s married to a Tunisian truck driver, and she has three children. She’s a housewife, but she doesn’t wear the veil. I met her when I arrived in Rome. We became friends immediately, and now we see each other practically every day, usually in the afternoon. We tell each other everything and we give each other a ton of advice. I often leave Aida with her when I have pressing things to do.

At eight I go home. After dinner I put my daughter to bed with a story. I’m not sleepy, so I decide to watch TV. I take a quick tour of the channels, using the remote. Nothing interesting on the Italian ones. So I try the Arabic. On a Lebanese channel I find a classic film with the legendary singer Abdel Halim Hafez and the actress Meriem Fakhr Eddine. It’s a love story about a young aspiring singer, desperately poor, and a beautiful rich girl. Soap-opera stuff? No, not at all. It’s a romantic movie with fabulous songs. It reminds me of my adolescence. I was in love, too. With whom? With a doctor, but he was married and had children. It was a platonic love, consisting of looks and a lot of fantasies. I’ve seen this film a bunch of times. I know all the details. Here’s my favorite scene. The two lovers are on the banks of the Nile. It’s night, the stars are out, Abdel Halim sings to his beloved Belumuni leh?, why do you criticize me?

Why do you criticize me?

If you, too, could see

Her eyes, so beautiful you could die,

It would seem to you right that I think only of her

And can no longer sleep.

Issa

The other day Mohammed the Moroccan received a strange phone call from the Rome police headquarters. He was told to appear the following day to receive his residency permit. He thought they were pulling his leg, but it was true. He woke at dawn so he’d be punctual for the appointment, assuming he’d have to wait in the usual long line for non-Europeans.

As soon as the office opened he went in to make inquiries. The agent, sitting behind a window with a tired and irritated look, merely entered the name in the computer. As he waited for the response Mohammed was very worried. Apart from that blasted telephone call, he had nothing, not a single scrap of paper with an official stamp, to bring as proof. Appointments are serious. You can’t just show up empty-handed. That’s how things work at police headquarters, commissioners’ offices, and checkpoints in airports. And Mohammed knows this very well, because he’s been in Italy since the eighties. Over time he has also developed a system of defense against possible reactions of police and municipal and postal employees, their use of the familiar tu rather than the formal lei, the sarcastic expressions, the ironic smiles, the provocative questions . . .

This time, however, it was different. The policeman said, with a big, broad smile, “Signor Mohammed, they are expecting you in the diplomatic office. Here, take your pass.” He couldn’t believe his ears. It was too strange. It seemed to him a sort of Candid Camera featuring not celebs but poor immigrants. Maybe he let slip to himself some comment like “What’s happening to me?” or “Bastards, they’re making fun of me,” or “I’m only dreaming and soon I’m going to wake up.” In short, he needed time to get used to words like “signor,” “diplomatic office,” and “pass,” since people in his category generally never heard them. You can’t change like that, point blank.

In the waiting room, he sat beside people with connections, people who count, the crème de la crème: families of foreign ambassadors in Italy, Russian and Chinese entrepreneurs, first-class non-Europeans (Americans and Canadians). He got a headache that lasted for the rest of the day. He felt out of place in every sense. And in the end he was issued a residency permit valid for two years. Until that moment he had been living in the nightmare of receiving a permit that was already expired. Now he could enjoy two years of peace.

Mohammed was still in shock. He couldn’t find any explanation for the phone call from the police and the warm welcome they had given him. He continued to speak of an inexplicable miracle. A providential intervention. He didn’t know whom to thank. God? Maybe, because last year he had observed Ramadan. His mother? Maybe, because he always prays for her.

I would have liked to reveal to Mohammed the true identity of his guardian angel, but I couldn’t. State secret.

I get in line for the bathroom. Luckily it’s not long. I dress quickly to go to the café for my usual morning cappuccino. Saber asks me to wait because he wants to tell me something important. Will he talk to me about Simona Barberini or about the Milan team? We’ll see. In five minutes we’re going out together. With him now I speak only Italian, I mean his Italian, with the “b” in place of the “p.”

“I’ve got something imbortant to tell you.”

“What?”

“There’s a sby among us.”

“A spy?”

“Yes, the bastard will be uncovered soon. We’ll bust his ass.”

“Who is it?”

“We have a susbect, but broof is lacking.”

“And who does he work for?”

“For that fucking whore Teresa.”

Shit, I practically had a heart attack! Worse, I was peeing in my pants. That would be the least of it in the face of this goddamn suspense. Saber explains that the “rat” has been employed by the landlady alias Vacation for a long time. So she knows about everything that happens here. The most serious thing has to do with the visitors who sleep in the kitchen. My fellow-tenants are afraid that Teresa will exploit this business to increase the number of beds, by adding a bunk bed to every room. She can come to us and say tranquilly, “My dear immigrant Muslims, you see? Sixteen of you can live happily and comfortably.” So she would have a new source of income, of four or five hundred euros a month. The hypothesis can’t be ruled out, given all the ads for exotic tours and low-cost cruises you see these days. More and more, this apartment resembles an overcrowded prison. The good news is that there’s another spy, although his duties are different from mine. In other words, a new colleague so I won’t feel alone. To each his mission. Hooray!

On the way to Little Cairo I get a text message from Judas. He wants to see me right away. Usually we meet in the afternoon. Why has he changed the plan? It takes me twenty minutes to get to Via Nazionale. Judas opens the door and asks me to follow him out onto the balcony to talk. He grabs a cigarette but doesn’t light it right away. During these weeks I’ve started getting to know him: when he’s nervous he prefers to stand up, preferably outside. Why does he do it? Probably to avoid the gaze of his interlocutor. He stands there and pretends to look at the passersby, the trees, the cars. A perfect way to hide his own emotions. To break the ice, I tell him about Mohammed’s adventure at the police station. He listens without saying a word. In fact he seems really annoyed.

“Anyway, I’d like to thank you for your help at police headquarters.”

“You’re happy for your Moroccan friend?”

“Of course—he was getting really depressed.”

“Wonderful! We’ve become two fine social workers. Instead of uncovering terrorists we’re saving immigrant workers from depression. In short, we’re just as good as Caritas volunteers!”

“Why did you want to see me?”

“To give you some good news.”

“What?”

“Dear Tunisian, your new friends in Viale Marconi are about to fuck us in a big way.”

“What do you mean?”

“We’ve received some disturbing information. In recent days fifty kilos of Goma-2 Eco have arrived in Rome, the same explosive used in the attacks in Madrid.”

; “Shit!”

“We’re looking for corroboration. If the information is confirmed we wouldn’t have time to stop them.”

We don’t say much because there’s not much to say. The situation is serious. I return to Viale Marconi distressed and terrified. The scenes of the victims of the slaughter in Madrid pass before my eyes without interruption. Something has to be done to stop the attackers. But what?

In the afternoon I go to Little Cairo. Every day I follow the same script. I call Tunis, and a woman’s voice answers, but not “mamma”’s. “Hello, little brother, it’s Amel.” It’s my “sister,” the pregnant one. It won’t be hard to talk. And in fact we devote the whole conversation to the baby. First of all, they have to find a name. Discussions are under way, but there is no shortage of problems. If it’s a girl her husband wants to give her the name of her dead grandmother. My “sister” is not totally in agreement.

“You think it’s right to give a child born in 2005 the name Saadia?”

“Certainly it’s not a fashionable name today.”

“I have no doubt of its great merit, since it refers to the woman who acted as mother to the Prophet Mohammed when he was orphaned. But should we look to the future or to the past?”

“The future.”

“See? You think the way I do. You wouldn’t call your daughter Saadia, either!”

The list of objections is extremely long. My “sister” is convinced that if the daughter (damn, she’s not even born yet) is named Saadia she’ll have an inferiority complex all her life and never find a husband. Poor Saadia won’t be able to compete with the Jessicas, Pamelas, Samanthas, Isabellas, etc. The Brazilian and Mexican soap operas are endless sources of names of all types and for all tastes. It’s just an embarrassment of choices.

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)

Divorce Islamic Style (9781609458942)